Reflections on Interiors: Luxury Resorts and Institutional ‘Safe

In this post, I am reflecting on two different interiors that share some commonalities: Luxury Resorts and workplace ‘Safe Spaces’. I find that both have a shared propensity for producing idealised, sanitised and utopian-like worlds in which uncomfortable realities are swept under the rug and replaced with more convenient ones.

Thoughts on The Tourstic Resort

To think this through, I want to recount an example of a tropical forest resort I stopped in for a day before continuing into a primary forest terrain. This resort was run by a foreign American entity. The utopian theatre in this space was emblematic of my interest. I will not name the country or the place specifically because that’s not the point.

You enter the resort and encounter a man dressed in particular clothing. It supposedly emerges from the local culture. Yet he is the first person you have seen dressed this way during your past few weeks of travel. A wide smile is plastered across his face, his dimples visibly shaking. He approaches you and utters a phrase in his language. You saw that exact phrase displayed on the airport walls in bold red letters – and in many other advertisements. This is the first time you hear it directed at you, but throughout the day, you encounter that phrase repeated fifty more times. Everyone is way too friendly.

Stepping into the chilly air-conditioned lobby from the humid outdoors, you are greeted by a large window framing a breathtaking sea view. As you draw closer, you take in the sloping hill leading down to the beachfront. The hillside is adorned with thriving and vibrant tropical plants, often described as “lush” in the resort’s promotional materials. The sheer density of colours and fruits within this small patch of land is truly remarkable. It is a picturesque representation of paradise.

The air is filled with the rich melodies of various bird species, which you also spot in a colourful array gracefully manoeuvring through the trees. Among the swaying vines, you catch a glimpse of monkeys swinging through. A nervousness creeps in; you turn to the receptionist and inquire, “How often do you encounter snakes?” With his solid smile, he responds confidently with an assurance, “You have nothing to worry about.”

Later in the evening, you wander around the grounds. You come across an employee driving a golf cart. He kindly offers you a ride back to your accommodation. His smile appears less polished compared to his colleague earlier in the day. The vibrant and perky enthusiasm you sensed in the morning now carries a tinge of unsettling sarcasm. You attempt to engage in a conversation. But you can not go beyond the usual script; the dynamic between guests and employees prevents deviation.

This was a stop before progressing into the primary forest; it is just a short distance from the resort location, approximately an hour away. These primary forests emerged from the earliest geological formations, so they have remained relatively untouched by modern physical human intervention. It must be even more colourful than the resort’s grounds, you think to yourself. However, as you enter, you notice a very different environment. Where are all fruits? Where is the explosive concentration of colours? You later discover that a high concentration of fruit-bearing trees would attract all wildlife to a single location, stopping their travel and thus the dispersal of seeds. The forest’s dispersal of fruit and flower is crucial to ensure its survival and balance.

Six hours into your hike, overwhelmed by the forest’s heat, you feel like you are on the verge of fainting. The equatorial sun pierces your skin sharply. Things no longer appear as cheerful. Animal carcasses and corpses become a common sight every kilometre or two. Poisonous snakes coil under leaves, preparing for their nocturnal hunt. A bite from one of these snakes can destroy human tissue in just fifteen minutes. Lizards engage in wild mating rituals, birds screech, and insects struggle to break free from the adhesive grip of leaves.

Curious, you ask the person accompanying you, “How come snakes don’t make it into the resort?” The man, who used to be a resort employee, responds almost mockingly at your naivety, saying, “They kill them if they slither onto the property.” You proceed to talk about work in resorts. He says things like: “Tourism is important, but…” “low wages”, “long working hours”, and “Drunk disrespectful tourists”. His words assure you of what you already know; chances dictate that those smiles were not real.

The truth is that luxury resorts are fundamentally experience economies; they must meticulously stage it all. This is what the consumer pays for; comfort and the silver spoon. But for this idyllic experience to be convincing, it must suppress life’s ‘ugly’ realities. Any potential threats, such as snakes, must be eliminated. Fruit trees must be selectively planted and artificially densified. The actual forest, potentially threatening humans, must be replaced with a version where humans can exist securely and comfortably. Even social realities need to be repressed. The employees’ genuine emotions and attitudes must be supplanted with a facade of unending happiness. In short, to craft a serene, idyllic nature and culture, the resort must necessarily suppress the actual natural and cultural realities, replacing them with carefully curated, convenient and polished appropriations.

It could be said these are just single isolated spaces, in which participation is optional – which may be true to an extent. But these idealised realities rarely come without cost. There is a lot written about the issues that surround tourism resorts, especially foreign investment chains like the one I encountered. These issues span environmental and economic impacts, many highlighted by my friend in the forest. Gated resorts of this sorts are commonly known to inflate the cost of living while contributing minimally to local businesses. With the one I visited, it had monopolised beaches and public spaces, gating these resources for an exclusive clientele.

These realities, unfortunately, do matter. In many instances, these resorts become the sole travel destination for a considerable group of tourists. The world of the interior becomes the sole representative of the place itself.

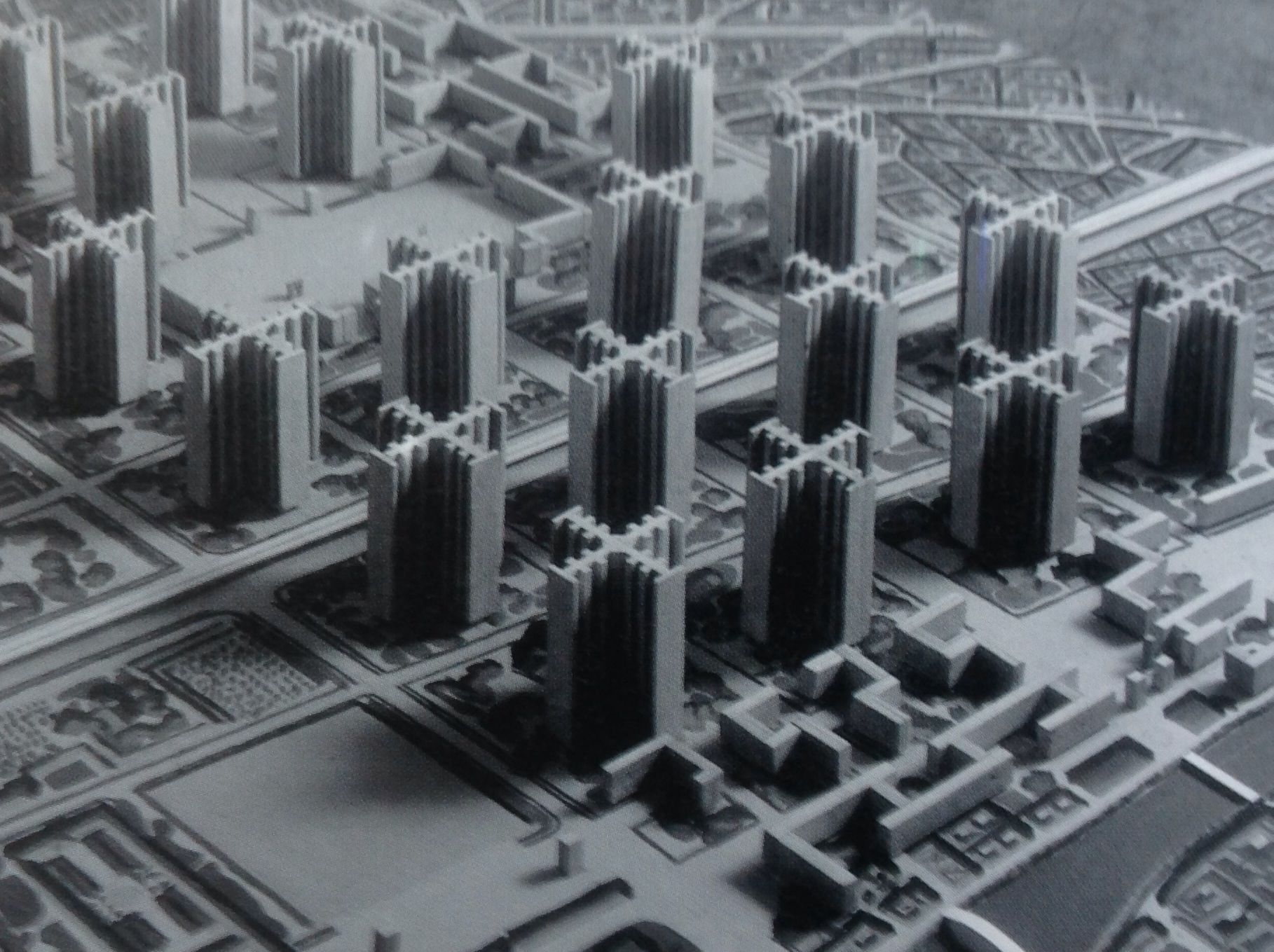

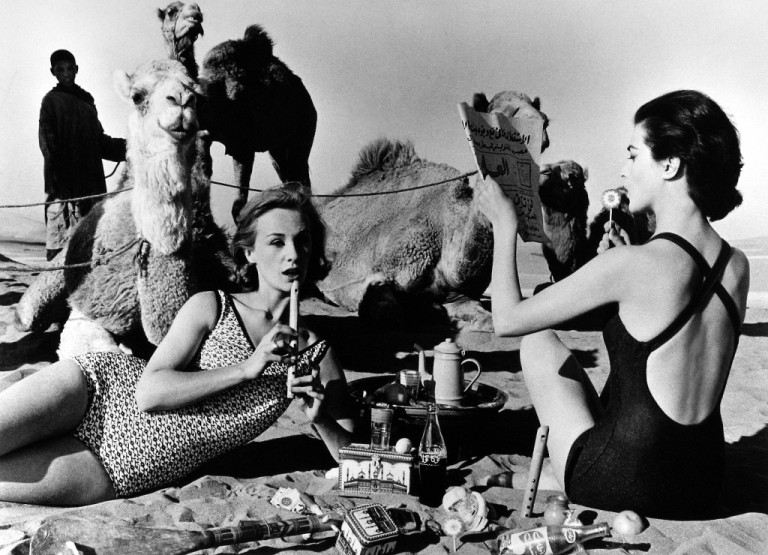

Examining the colonial antecedents could shed additional light on this phenomenon. Consider, for instance, the resort typology in colonial history, particularly British resorts in the colonies of Egypt and India, or French resorts in North Africa. These establishments aimed to create clearly designated spaces for Western travel, where the space of the coloniser was explicitly segregated from that of the colonised. This was done through a construction of luxury spaces in a territory being actively extorted under colonial rule (the resorts of course also operated in this extortion). These spaces not only obscured the reality of violence under colonialism but also perpetuated orientalist perspectives that reinforced the coloniser’s sense of superiority and framed the natives as inferior or exotic. This segregation is not vastly different from many contemporary resorts, which are meticulously designed to cater to the whims and desires of tourists. This design often limits encounters between tourists and natives to engagements with reductive appropriations of the ‘local culture’ or as service encounters.

With all of this said, perhaps it would be less of an issue if this detachment and idealisation were only limited to a selection of designated consumer spaces. However, I do not believe this drive for idealising fiction is unique solely to bespoke consumer experiences but can be more widely observed in other contemporary spaces.

Thoughts on The Institutional ‘Safe Space’

There is an unsettling de-ja vu in this act of distortion to other spaces in a modern metropolis like London—even in spaces which aren’t conventionally seen as spaces of consumption, like the institutional workplace. The manipulation of reality to create an idealised world is one which I see for instance in the institutional idea of the ‘safe space’.

As a participant in academic environments, university space, particularly my workplace, is an interior environment with which I am closely associated. Therefore the notion of ‘safe space’, in an institutional sense, is one which I encounter often. I should clarify that the ‘safe space’ term I’m referring to here is not the term commonly used to denote the crucially important spaces of solidarity or refuge for those exposed to danger, racism, or abuse. Instead, I’m addressing what I see to be its institutional co-option by liberalism.

Although this is a space that corresponds to a physical institutional workplace or university environment, it is more of a conceptual interior. I mean this more in the sense that this ‘safe space’ is designed and produced primarily through administrative policies and training programs. There is generally something behind its making like a Human Resources department or a related administrative department within the university.

Although of older origins, this concept of space became particularly important after institutional panic following the protests surrounding George Floyd’s death. At that moment, there was an attempt made to rebrand spaces as ‘decolonised’ with an amalgamation of inclusion, diversity and equality initiatives and ideas, ultimately producing in many institutions what is a palatable version of the decolonisation movement. This has not only resulted in a misleading reaffirmation of pre-existing liberal principles. But much like the resort has done to pacify the forest, this space works to mask the reality of colonial struggle and subdue it into a neatly ordered and passive consumable reality.

There is a lot to discuss concerning this matter. But to try and illustrate a small facet of this point, I want to share a few examples from an “unconscious bias” training I received a few years ago. This training is part of a series of modules intended ‘to foster a safe environment’. This type of training, I understand, is also given in other workplaces. “Unconscious Bias”, institutionally speaking, refers to the unconscious decisions and judgements derived from one’s past experiences and deeply embedded cognitive patterns. Therefore, what this training claims to do is heighten an individuals’ awareness of these patterns to prevent discrimination and prejudice.

7

Here are some examples from the online training I participated in:

Example A: The following example was provided:

“I experienced a rather strange sensation as I boarded the plane. I noticed that the pilot was black. I had never seen a black pilot before, and the moment I did, I had to suppress my panic. How could a black man fly an aeroplane?”

The lesson then posed a multiple-choice question: Who do you think said this statement:

A) Jackie Kennedy B) Nelson Mandela C) Enoch Powell D) Audrey Hepburn E) Harold Macmillan

Upon revealing that Nelson Mandela was the one who made the statement, the training module underscored the point that everyone experiences unconscious bias, even anti-apartheid advocate Nelson Mandela.

Example B: An animated video is presented featuring Taylor, a white man, entering what can be assumed is a cafeteria. Upon noticing a large group of people of a different racial background than his, he decides to sit at a predominantly white table.

The training uses the scenario to underscore that people often tend to foster better links with their ‘in-groups’ (people who share your background) at the expense of ‘outgroups’ (people who don’t share your out-groups). Taylor, should’ve made a conscious effort to reach out to the ‘outgroup’.

A quiz follows at the end of the training, posing another hypothetical situation:

Jayden, who is black, observes two groups of people socialising. One group consists primarily of people from his racial background, while the other is a mix of ethnicities. In an ideal scenario, what should Jayden do?

A) Join the group with more people from his racial background.

B) Attempt to merge both groups.

C) Join the mixed group.

The correct answers are B and C.

These examples share a commonality: they divorce themselves from context and circumstances. They instead establish a hypothetical world in which everything is already equal. In the Mandela scenario, historical and contextual circumstances are entirely disregarded. What Mandela attributes in his biography to the internalisation of colonial racism and violence has been simplified in this unconscious bias training into an issue of universal human nature that affects everyone regardless of experience or background. The brutality and violence of the colonialism that birthed this racism are sidelined. Instead, the burden of racism is uniformly assigned to all equally.

What is most concerning, however, is the parallel drawn between Mandela’s knowledge and the instruction of the training. The implication is that what Mandela talks about is somehow synonymous with the ideas imparted in this unconscious bias training. There is a suggestion that these two conditions have a shared origin of sorts, and that the depth of what Mandela has struggled to learn can, in turn, easily be conveyed through these simple set of instructions. It would certainly be convenient if that were the case.

In the second example the issues are oversimplified into extremely abstracted and algorithmic equations. My objection lies with the entirety of the question which I find to be way too simplistic and reductive. It is genuinely challenging to empathise with the situation without comprehending the circumstances. Yet, even acknowledging the incompetence of the question, there are in my opinion numerous valid and compelling reasons for individuals to seek the company of their racial background, particularly if they belong to a historically marginalised group in the West.

Similar to the first example, the second attempts to put forth universal principals that completely disregard relative situations. Part of being able to do this, entails that the active situational power dynamics and relative dispositions formed by colonialism must be flatly denied. Instead it is replaced with a ‘utopian’ scenario in which everyone is already equal, with perhaps only a slight difference, that it claims we should be critically aware of, between people – ethnic background and skin colour. Racism here is completely stripped out of its colonial reality and ending it is presented as a simple case, equally applicable to all, of being aware of human nature’s innate resistance to colour and difference.

Establishing this ‘safe space,’ an interior aiming to develop a new, unbiased, non-racist environment, utterly severs itself from the active racialized realities shaped by colonialism and Western imperialism. Instead, it opts to construct an abstract, orderly, bubble-wrapped utopia where everything is conveniently and suddenly already equal, and the issue is just a matter of upholding this balance. To achieve this, needless to say, the realities of racial inequality and struggle must be suppressed.

Further Questions:

Primarily, through their disconnection from reality, separation from circumstances, and their construction of utopian-like worlds, it is as if these spaces – the resort and the ‘safe space’ – claim that they do not belong to the same reality as the outside. Reality seems to be suspended within these spaces.

In the luxury resort, the same employees observed outside with everyday emotions are portrayed as perpetually joyful inside. Similarly, the forest, which has the active power to threaten and de-center humans, is made to be a tranquil, pristine and peaceful haven. In the ‘safe space,’ the reality of western colonialism and its lasting and active impact on societal structures is seemingly nonexistent – ironic since these interiors have been instrumentalized to respond to a colonial matter. Instead, inside this interior, racism is selectively admitted whilst masking the colonial realities in which it persists.

Of course, these realities are not suppressed with simple concealments, but with power. How long will it be before the realities reprised by these interiors shatter the idealising illusions of these bubbles?

What impacts do these distortions have on those who inhabit them continually?

Is there a wider epistemological origin that binds these spaces together?

How is it that interiors, and their associated reproductions of reality, can heighten instead of dampen our sense of reality.